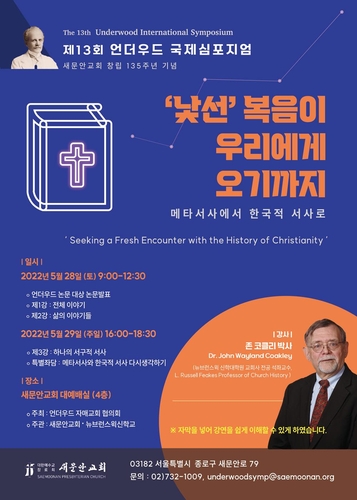

13th Underwood International Symposium

May 28, 2022

After a two-year hiatus, the Underwood International Symposium reopens May 27-June 1 with our own professor emeritus, Dr. John Coakley, as the keynote speaker. He will deliver a series of three lectures on the theme of Seeking a Fresh Encounter with the History of Christianity at the Saemoonan [se-mun-an] Church in Seoul founded in 1887 by Horace G. Underwood (1859-1916), who graduated from NBTS in 1884 and was the first Protestant missionary to Korea. Afterward, Prof. Coakley will give additional lectures at the various NBTS’s affiliate institutions founded/initiated by Underwood, such as Yonsei University, Jangsin Presbyterian Seminary and University, and Soongsil University.

NBTS President Micah McCreary is also in Seoul as the NBTS host for the event, and will be delivering several sermons and speeches at the Saemoonan Church, Luce Chapel at the Underwood International College at Yonsei University, and Seoul-Jangsin Theological University. He will also meet with their respective Presidents and Deans to discuss further cooperation between the institutions and programs, as well as meet with prospective students interested in studying at NBTS.

Abstracts from Dr. John Coakley’s lectures:

The Underwood Symposium, Seoul, 2022

“Seeking a Fresh Encounter with the History of Christianity”

“Seeking a Fresh Encounter with the History of Christianity”

About The Lecturer

John W. Coakley is the L. Russell Feakes Professor of Church History, Emeritus, at New Brunswick Theological Seminary in New Jersey, U.S.A., where he taught for thirty-two years before his retirement in 2016. He received his academic degrees from Wesleyan University (A.B.) and Harvard Divinity School (M.Div., Th. D.). Before beginning his teaching career at New Brunswick, he served as a pastor for ten years in Congregational churches. He is a General Synod Professor, Emeritus, in the Reformed Church in America. As a scholar of the history of Christianity, he has specialized in the study of medieval spirituality, but has maintained wider interests as well, reflecting the scope of his teaching, which has extended to the whole of Christian history. His publications include Women, Men, and Spiritual Power: Female Saints and Their Male Collaborators (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), New Brunswick Theological Seminary: An Illustrated History 1784-1014 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014), Readings in World Christian History: Earliest Christianity to 1453 [with A. Sterk] (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2004), and many scholarly articles, including “The Seminary Years of the Missionaries Horace G. Underwood and Henry G. Appenzeller, in Korea Presbyterian Journal of Theology 47 (2015): 59-82, which originated as one of the lectures at the Underwood Symposium of 2015.

Lecture I: “The Whole Story”

The first lecture poses the problem of conceptualizing a “metahistory” of Christianity, that is, a comprehensive narrative of the Christian movement over time. In Europe and North America, until recently, historians tended to work from an implicit metanarrative that traced the Christian movement from its origins in the Mediterranean basin to Western Europe and then to North America, considering other manifestations of Christianity as peripheral to that main narrative. But by the late twentieth century, critiques of that approach, and indeed of the possibility of any such overarching narrative of Christian history, were mounted, for example in the proposal of the scholar Dale Irvin that the history of Christianity should be written not as a single narrative but as many distinct narratives – as, in effect, the histories of Christianities. The remainder of this lecture explores the work of two scholars who have laid a foundation for reclaiming a metanarrative without allowing any strain of it to obscure the others: Lamin Sanneh and Andrew Walls. Key to the work of both is the insight that Christianity is by its very nature, beginning with the early church’s spread into Greco-Roman culture, a translated religion which, unlike Islam, takes root in new settings specifically by communicating its message in the cultural idiom of those who will hear it. This is a principle that, on cues from Walls in particular, might serve to shape a metanarrative of Christian history that does not run the risk of making one culture-bound tradition into the norm for the others, in three ways: first, by connecting Christian history to the Christian message itself, in the doctrine of the Incarnation, understood as a translation of God’s very self into human form and consequently God’s entry into the particularities of culture; second, by highlighting and helping to explain the “serial” nature of the history of Christianity, whereby it typically rises and declines in given settings in consequence of its success or failure in the continuing task of cultural translation; and third, by focusing attention on the tension within every given form of Christianity, between its own encounter with its culture and its critical assimilation of an “adoptive past” of the history of other Christians, as a universalizing factor in its identity.

Lecture II: “Life-Stories”

The second lecture discusses two evolving themes in Christian biography in the Western Middle Ages. Framing these in pedagogical terms as an exercise in encountering the past through forming a critical personal relationship with it, the lecture illustrates, in medieval examples, the phenomenon of the translation of Christian faith in cultural terms that the first lecture treated in a more general way. The first theme is that of “constancy and conversion.” Here the starting point is the classic biography of the ascetical but socially active bishop Martin of Tours, written around 400 A.D., which, in contrast to many biblical stories, but in continuity with Greco-Roman biographical traditions, pictures its hero as “constant,” i.e., unchanging, in virtue, but it also, in discontinuity with those traditions, introduces Christ as a presence throughout the hero’s life, adopting a narrative structure that includes a new transcendent dimension. Then toward the end of the Middle Ages, in 1228, an equally famous early biography of Francis of Assisi models Francis on the figure of Martin in his social activity and his asceticism and retains the presence of Christ in the narrative, but pictures Francis now as a repentant sinner, thus abandoning the Greco-Roman ideal of constancy for an interest in the inner life of the individual that was consistent with trends in late-medieval culture that anticipated the Renaissance. The second theme is that of “gender and authority.” Here at issue is the biographical representation of women. Once again, we see early Christian biography making use of earlier Greco-Roman literary conventions: the examples are the second-century “Acts” of Thecla, a fictional female disciple of St. Paul, and, though in a more ambiguous way, the third-century martyrdom account of Perpetua of Carthage. The biographers present these women as essentially male in their virtue, strength and authority, drawing on the idea found in Plato and other ancient Greco-Roman philosophers that construed men as superior to women and imagined a perfected woman therefore as becoming, in effect, a man. And a late medieval example shows the abandoning of that Greco-Roman idea: this is the thirteenth-century biography of Mary of Oignies, in which virtuous behavior of a woman is presented as distinctively female, reflecting and complementing certain cultural developments of the time, including the assertion of a uniformly male ecclesiastical authority by the so-called Gregorian Reform movement, and, once again, the interest in the interior life of individuals, which would shortly come to fruition in the Renaissance.

The conclusion of the lecture alludes to the evident relevance of these themes for our own lives and situations, but also to their strangeness to us insofar as they reflect their own cultural contexts; and it suggests that our encounter with the Christian past is a matter of keeping these two aspects of the Christian past in tension with each other.

Lecture III: ”A Western Narrative”

The third lecture examines some roots of the modern Protestant world mission movement, taking the American pastor and theologian John Henry Livingston as a representative figure. Livingston, who received his theological education in the Netherlands, was a pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church in New York City, and in 1796 became one of the founders of the New-York Missionary Society. His approach to missions was shaped by the ideas of the so-called Enlightenment, in its moderate Christian form, with an emphasis on Christian faith as consistent with reason and as in fundamental harmony with the notions of freedom given expression in the American Revolution. These ideas in turn had roots in the long history of Western Christianity – that is, in the particular “translated” form of Christianity that had taken distinctive shape in the Middle Ages and had undergone a major turning point at the beginning of the modern era, in a cultural shift that had favored ideas placing human beings at the center of the cosmos. The conclusion of the lecture comments once again on the double way in which we encounter historic Christianity – that is, how we find ourselves both embracing it and holding it at a distance, as, in this case, in the spirit of Walls’s notion of the critical acceptance of an “adoptive history,” we may affirm the centrality of the church’s call to mission, and admire those who followed it in their own place and time, even as we may not share the culturally rooted assumptions on which they did so.