Shelter and dwelling: A pandemic response to houselessness and community-engaged pedagogy in theological education

September 8, 2023

by Nathan Jérémie-Brink

Abstract

Created during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Shelter Project brought together a denominational seminary, a leading state research university, a community arts organization, and a housing non-profit serving unhoused and vulnerable neighbors. As the pandemic revealed and intensified the ongoing crisis of houselessness in central New Jersey and across the United States, this project, funded by the Henry Luce Foundation, provided direct housing services, preserved the stories of unhoused and vulnerable neighbors, and offered public arts interventions promoting engagement and advocacy. This article reflects on the Shelter Project’s collaborative community engagement, demonstrates how oral histories and public arts developed a project-informed pedagogy, and argues for more projects that employ community-engaged scholarship in theological higher education.

1 INTRODUCTION

Religious and educational institutions have opportunities to change how we consider the work of social justice and community in response to houselessness and economic injustice. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed intersecting vulnerabilities that leave many across the United States and in our local community unhoused. Even as the pandemic fades from public consciousness, those vulnerabilities remain. Further, calls for reckoning with racial injustice in the United States such as the Movement for Black Lives and protests against anti-Asian hate have highlighted how dispossession and economic inequity reveal disparate and racialized realities. These factors lay bare how understandings of property, rights to land, and the concept of home in American society are shaped by race, class, and geography. Yet these present crises also invite new approaches to the needs of those most vulnerable in our communities. They also invite scholarship and teaching rooted in collaborative labors for radical social change. Houselessness is a topic that offers a relevant and critical consideration of how theological education might teach about intersectional oppression and engage in justice work.

The intersectional vulnerabilities behind the crisis of houselessness reveal immediate needs for service and demand more from theological educators and religious institutions than shallow models of charity or benevolence. We must boldly identify historical and social structures of oppression and challenge hateful systems in our society that disinherit those among us who are poor, non-native born, Black, queer and/or transgender, survivors of abuse, ill, and disabled. I argue for the importance of community-engaged scholarship in theological higher education and offer the Shelter Project as a model for teaching about the crisis of houselessness that used art and oral histories to disrupt traditional academic patterns of scholarship and teaching in favor of community accountability. Our efforts to decenter the voice of the scholar and learn from and with our neighbors, advocates, and artists created a projects-based collaborative community with the potential to move beyond mere social commentary and reshape classrooms, curricula, and institutional life toward transformative participation in local efforts toward justice.

2 SHELTER: DIRECT AID AND COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP

This focus on poverty and the housing crisis and my reflections on community-engaged collaborative scholarship in theological institutions and higher education more broadly draw upon the experiences of the Shelter Project, a collaborative direct service, public arts, and humanities project of New Brunswick Theological Seminary (NBTS), Rutgers University–New Brunswick, and coLAB Arts New Brunswick, all based in central New Jersey. This project was generously funded by the Henry Luce Foundation through an emergency grant from the program in Theology and Religion. While the project began in response to the COVID-19 pandemic delivering funds to house and provide for the basic needs of the most vulnerable of our neighbors, it has expanded beyond the scope of the original project as we think and teach and publicly advocate using the materials the project generated.

At the height of the pandemic, the Henry Luce Foundation awarded NBTS an Urgent Needs Grant of $150,000 through their Theology and Religion program. The express purpose of the funding was not to advance research on the subject but merely to offer immediate and direct aid (The Henry Luce Foundation, 2022). Other recipients of such grants from the Luce program in Religion and Theology included diverse institutions from across the United States, ranging from universities such as Arizona State, New York University, Brandeis, and Morgan State to graduate theological institutions including Graduate Theological Union, Vanderbilt Divinity School, Brite School of Divinity, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, and Chicago Theological Seminary and even one secondary school, the Santa Fe Indian School Leadership Institute in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In web conferences and communications with this cohort of grantees, it was obvious that the task of aid responsive to community needs opened institutions up to providing material support for neighbors. This in turn cultivated thinking and scholarly work that cut against structures of privilege and the sectarian and cultural matrix that too often tend to silo the work of academic institutions.

In our specific case, in talking with our community partners, we soon realized that the so-called housing crisis (itself the product of complex political choices made over many years) was a common thread among our community non-profit partners, regardless of their institutional mission or the clients they served. Accordingly, NBTS passed most of its grant money on to the Reformed Church of Highland Park Affordable Housing Corporation (RCHP-AHC) to provide direct financial assistance to more than 120 people. The grant helped 32 households secure housing and assisted some recipients with case management support, including legal and social services related to domestic violence, early release from prison, and immigration.

Listening to our community partners, we learned that the need for emergency support for housing was most acute when we began the project but that housing and houselessness were also “lenses” through which we could keep in view a broad range of social and economic vulnerabilities. For example, lack of access to long-term housing options impacted domestic violence shelters overcrowded during the pandemic, those caring for survivors of human trafficking, and immigrant and refugee resettlement organizations trying to house recently arrived people or those furloughed from immigrant detention centers due to the high COVID case counts in those prisons. New Jersey’s early release of many incarcerated people from state prisons during the pandemic also exacerbated the channels for supportive housing for these returning citizens. The moratorium on evictions unevenly protected residents of New Jersey, with the most vulnerable, poor, or ill often not receiving adequate protections and being forced out of their housing. The public health crisis also complicated the safety and health of the long-term unhoused population in Central New Jersey, many of whom fell through the cracks of other social benefits or support systems.

Care for the most vulnerable in our community was the project’s first and guiding concern. But linking up with the Affordable Housing Corporation and other community partners doing this work was integral to our second phase of the project as well, in which we considered how we might preserve and interpret these experiences of our unhoused neighbors and cultivate resources for our students and the public to gain awareness of these issues.

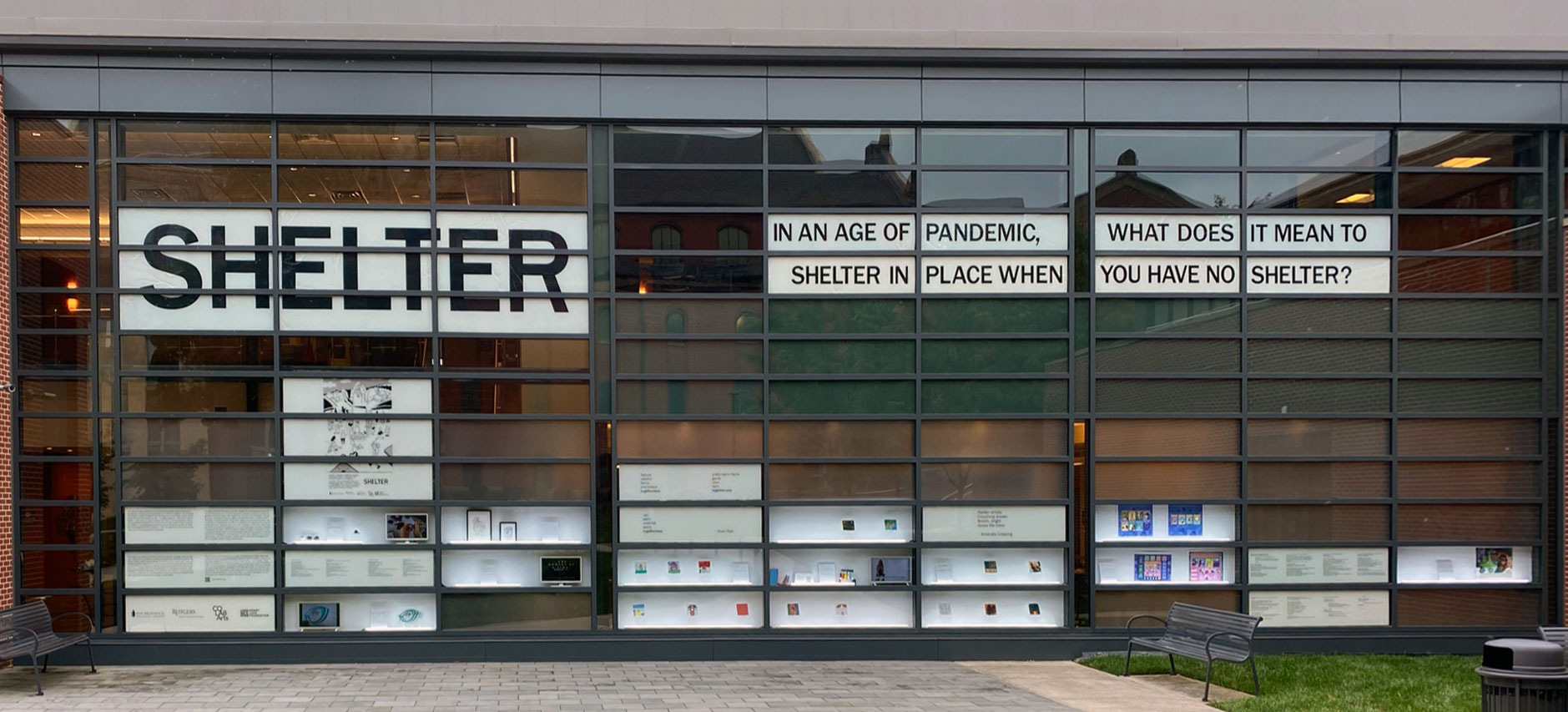

To begin with, COVID-19’s early devastation of the New York–New Jersey metropolitan area meant that we conceived of the project while under public health orders to “shelter in place.” It was a common reflection that the concept and the physical spaces of home began to change under these constraints, in new and challenging ways. The project’s central interpretive question was born of the moment but attuned to the experiences of the most vulnerable: In an age of pandemic, what does it mean to shelter in place when you have no shelter? Moreover, the experiences of vulnerability that resulted in the lack of this most basic human need and right continued to open our investigations out toward analysis of broader structural realities. At this point, a second phase of the project began to take shape, in which we were not merely triaging immediate needs. Colin Jager, who directs the Center for Cultural Analysis at Rutgers, brought to our leadership experience and contacts in organizing interdisciplinary arts and humanities programming. The interdisciplinary humanities and public arts interventions we subsequently undertook through the project thus marshalled the range of disciplines and approaches represented across our directors and institutions.

Historians on the project worked with students and non-profit case managers to preserve the experiences of housing-insecure members of our community through oral histories. Consistent with the practices of the Rutgers Oral History Archives, this effort did not require internal review board approval and allowed us to develop protocols that worked within the scope of our project. My colleague Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan in the Rutgers History Department drew upon her experiences as a specialist on the history of homelessness and a scholar of the public humanities. She arranged a partnership with the Rutgers Oral History Archive to train Rutgers and seminary students to conduct oral history interviews. For this project, O’Brassill-Kulfan and I decided against a traditional life course oral history model in favor of interviews that deployed a set of open-ended questions asking about the participants’ particular experiences of the pandemic, housing challenges or perspectives, the meaning of shelter or home, their reflections on religious traditions or spiritual practices, and their thoughts on community.

Conducting these interviews while pandemic-era restrictions continued was a significant challenge, since much of the work had to be done virtually. After interviews were conducted, student research assistants provided annotations, linking elements of the individual participants’ personal stories to academic and news sources contextualizing issues like mental health, domestic violence, incarceration, affordable housing, and other key topics discussed in the oral histories. Using individual oral histories as a lens to see broader structural vulnerabilities and injustices created resources for the program that preserved and honored each person’s experience. In addition, annotating those oral histories created complex resources that set individuals’ experiences against a broader social context and at the same time delved deeply into our neighbors’ struggles, laments, resilience, and joys.

Rather than immediately turn to analyze these oral histories within the humanistic disciplines of history, theology, and literature in which our co-directors at NBTS and Rutgers were trained, Dan Swern at coLAB arts facilitated artistic interpretation of these experiences by community-based artists. These submissions featured a range of media that highlighted aspects of our unhoused neighbors’ experiences. Themes included hope for social change, perseverance, and understandings of the ways people and our society at large looks away from the poor and marginalized. Artists also offered art that commented on why people and institutions often fail to intervene in systems of structural vulnerability, exploitation, and disenfranchisement. Artists celebrated and reinterpreted testimonies of meaning, community, spiritual growth, and hope.

Local artists interpreted complex stories of struggle and resilience through various media including poetry, drawing, painting, theater, and movement. Our digital site (www.ShelterNJ.org) housed not only the annotated transcriptions but also artistic interventions that meditated on and interpreted those experiences and perspectives (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2

To promote community engagement, the Shelter Project also created a large-scale art installation that exhibited the initial interpretive works drawn from the direct service and participant oral histories. The multimedia installation took up an entire side of the seminary building that faces both the main courtyard of the seminary and the central quad of the university and was on display through December 2021 (Figures 3–5).

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 5

The public art installation displaying these interpretive works opened on September 18, 2021. In addition to the project co-directors, Rev. Seth Kaper-Dale, director of the Affordable Housing Corporation, spoke about ongoing community needs and underlying causes of housing insecurity. He stressed advocacy for structural change and direct aid interventions. Faculty, staff, and students of NBTS and Rutgers, community partners, and families came out to support the launch of the exhibition. The event also featured live performances of dance and theater pieces based on the oral histories of participants who received housing through the grant.

In addition to the public advocacy around this issue that the art installation promoted, the project team incorporated the Shelter Project into their teaching at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Courses taught by the NBTS and Rutgers University faculty featured the installation to engage with the stories of people in our community facing housing insecurity and to consider how religious and academic institutions might respond. Project co-director O’Brassill-Kulfan, who is a historian of poverty and houselessness in the United States, incorporated the project into a Rutgers undergraduate course on homelessness and unhoused populations in US history. In that class, more than 100 students explored the oral histories and other content generated through the Shelter Project to help them understand local contemporary dimensions of poverty and housing insecurity.

Another teaching intervention featured the collaboration of co-director Swern and Rick Anderson, who directs Virtual Worlds and the Game Research and Immersive Design (GRID) Group at Rutgers. They worked with one artist, Mason Beggs, on a digital board-game-style experience (Figures 6 and 7). Their class used this teaching tool to explore some of the challenges faced by people who are housing insecure. While the cases were anonymized, they helped foster student interest and classroom conversations around the complex struggles, varied goals, and individual resilience of our unhoused neighbors.

FIGURE 6

FIGURE 7

Another Rutgers class that used the installation was the Fusion Yorcha dance class of Professor Alessandra Williams at the Rutgers Mason Gross School of the Arts. Students were able to hear about the direct service project and experiences of unhoused people, reflecting on the physical challenges of those who are unhoused and vulnerable even as they danced outdoors, exposed to the elements and in front of the arts installation.

An additional output of the project was the Shelter Podcast, designed for general listeners and students. The podcast introduces the problem of housing insecurities in a time of pandemic and the role academic and religious institutions can play in partnering with the community to find solutions. The episodes are available at the project site and other major podcast distribution services. It is produced by award-winning radio journalist Scott Gurian and narrated by Scott and Diana Molina and developed and edited by Shelter Project co-directors. It features community producers who include both NBTS and Rutgers students, as well as community members who have experienced housing insecurity. In addition to the broader questions it raises, it explores briefly our local context, where this project featured the unusual partnerships between a research foundation and local direct service non-profits, conducted by a collaboration between a state research university and a denominationally affiliated theological seminary. The idea behind the podcast was for a resource that might outlast the art installation and prove useful for ongoing pedagogical interventions across Rutgers and NBTS courses but also be accessible enough that general listeners or even project participants could engage this imperative issue. The New Jersey Society of Professional Journalists named the Shelter Podcast Best Podcast in the Digital Division in December of 2022.

The leadership team of the project also discussed the iterative process of the project’s methodology, the public impact of the installation, and the development of the podcast at the Rutgers University Graduate Public Humanities Conference in April of 2022. This process of collaborative community-engaged scholarship has been transformative and exciting for me as a scholar. It has required more integration of the various aspects of myself: as a historian, an ordained Presbyterian minister, a member of local church and community organizations, and seminary professor. Interestingly, while my own skills and passions were more integrated through this project, the outcomes of the project featured the preservation of an archive and presentation of a diverse range of artistic interpretations that extend far beyond my own voice, discipline, and social location. The project’s work puts service to the most vulnerable front and center. It has developed resources that acknowledge and celebrate those members of my community in ways that honor them and promote deep learning, prompting lingering questions about how the seminary and university might approach issues of community and social justice.

3 DWELLING: HOUSELESSNESS AND SOCIAL JUSTICE IN THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION

Shelter is a basic concept. Understood as a person’s right to a safe place to dwell, stay, and sleep, shelter is often enumerated among the most fundamental human rights as a necessary provision for life. Because it is such an obvious feature of our material needs across time, geography, and culture, the concepts of shelter and home also have powerful meanings in a range of religious traditions. Many sacred texts across religious traditions invoke the role of the divine in providing safe dwelling or in leading journeys from displacement to home. Where and how one finds a home, or where and how the divine may dwell among humanity, the importance of shelter and home is intimately entwined with our understanding of God.

Several scriptural traditions also demand that people care for those who are poor or displaced or who lack shelter, and some texts present God’s preferential option for the vulnerable and oppressed. The 58th chapter of Isaiah in the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian Bible presents the substance of religious observance rooted in care for the hungry, naked, poor, dispossessed, exiled, and unhoused. Isaiah suggests that if they act justly on behalf of the most vulnerable, God will return the exiled Hebrew people to their lands and homes and grant them restoration and flourishing. The Acts of the Apostles too describes how early participants in the Christian movement sold their possessions and held resources in common and how networks of women led the community’s care for the poor and vulnerable. This is a vision of mutual aid and radical communitarian accountability as a foundational principle of the early Christian movement.

In many instances, faith communities and institutions of higher education in theology and religion have the opposite problem. To be sure, many faith communities take seriously a responsibility to vulnerable neighbors and are engaged in measures to provide direct service or care for poor, marginalized, or unhoused people in their communities. Yet many of these communities (and especially those whose communal experiences and theologies are embedded in Whiteness and economic privilege) do so in a shallow articulation of Christian charity. Often, these efforts are the antithesis of bold calls for social change and rather tend to blunt criticisms of structures of privilege that cut across issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality. The call to compassion and acts of service play to neoliberal assumptions and a politicized American exceptionalism that identifies poverty with poor individual choices and that positions religious and non-profit voluntarism as the only acceptable alleviation.

Most North American institutions of theological and graduate religious education are even more disconnected from direct measures to provide for the most vulnerable. This is despite a shift in recent decades toward fostering critical thinking about issues of faith in society. Despite antiracist and inclusive perspectives, a more robust sociological analysis of religion, and a greater acknowledgment of liberation theology’s framing of God’s “preferential option for the poor and oppressed,” too many institutions remain tethered to the limitations of local religious bodies or remain rooted in theologies and practices of Whiteness. I am neither suggesting a clean division between scholarly and experiential knowledge nor asserting that sources assumed to fall into such divided categories track across a white/Black or oppressor/oppressed binary. However, there is a challenge within institutions built to foster academic knowledge and the written word in terms of those institutions’ distinct limits in their ability to cultivate responsive relationships with their communities or public project. Many academic disciplines, including the traditional humanities fields that dominate theological higher education, struggle with the appropriate way to receive the testimonies of our neighbors or how the embodied experiences of people facing social vulnerability or oppression force reconsideration of our epistemologies and pedagogies.

Institutions of higher education also tend to conceive of public engagement as a class-restricted proposition, assuming that research and writing and speaking in academic circles suffice as public labor without interrogating the general inaccessibility of our disciplinary jargon, the prohibitive costs of our books and journals, and the insularity of our participation in the debates and forums of field and guild. Because direct care for people is generally outside the missions of seminaries and divinity schools, it is no surprise that these institutions rarely consider the unhoused or the available mechanisms for direct aid or community-engaged learning around these subjects, nor is it a surprise that they rarely participate in innovative strategies to support these efforts.

More than half a century since Gustavo M. Gutiérrez argued that “theology comes ‘later’” after a more primary “commitment to charity, to service,” his words remain challenging to higher education where theology is necessarily an academic discipline (Gutiérrez, 1970, pp. 244–245). His commitments to a theology linked to praxis, reflective of action and committed to social and economic transformation of the world, are studied in courses of religious history, theology, and ethics yet, for all their invocation, seldom translate to seminaries and schools of theological education engaging in the kinds of praxis that would bolster or inform their academic knowledge production around social justice.

The Shelter Project has sharpened my own conviction that theological education must move in the direction of community-engaged scholarship and a pedagogy that connects with and learns alongside our most vulnerable neighbors and the direct service partners and community advocates and artists who might assist us do so. This willingness to engage in projects that test our commitments to liberative praxis is necessary if we are to take seriously the teaching of Latinx, Black, feminist, womanist, and queer theology. In my own institutional context, it is also essential to pursue an approach that is responsive and responsible to our students, who are predominately students of color and majority Black. Many of them are engaged in church and social organizations that take social responsibility seriously as a bedrock for the study of theology. There has long been a call for theological educators to contend with these prophetic witnesses, often by those least empowered in institutional structures that privilege Whiteness and property. The Black Presbyterian minister and historian Gayraud Wilmore (1983) wrote that “Black Christians continue to demand from us the kind of scholarship that can, at one and the same time, deal honestly with facts, uncover truth, and lead the reader toward a religious commitment to help remake the world and not be satisfied simply to dissect it” (p. xii). Professional academic and institutions of higher learning need to hear from those who are unhoused and who have been dispossessed of rights and material needs due to oppressive social structures. More than that, they need to respond to what they hear with theological sensitivity and radical openness to change.

One of the rare theological books that consider houselessness, Susan Dunlap’s (2021) monograph, Shelter Theology: The Religious Lives of People without Homes shares some methodological and interpretive ground with the Shelter Project. Dunlap’s published theological work is deeply rooted in direct service—in her case, in the Hayti neighborhood of Durham, North Carolina. Her chaplaincy has been oriented toward the unhoused and principally to meeting immediate physical needs while remaining attentive to how the unhoused think critically about survival and ethics and make meaning in ways attentive to religious and material considerations. One of Dunlap’s chapters, like the Shelter Project’s Oral Histories, takes time to record and share the narratives of the unhoused. In her examination of two unhoused people who shared what she calls “resistance stories,” Dunlap identifies diverse approaches to life stories and future trajectories that share a conferral of “full humanity and hope” upon them and testify to thanksgiving and faith. She comments that their stories

relate moments of subversion of larger systems of power. They tell counterstories that include humanizing, dignifying, and often-disregarded facts and perspectives that contrast with the stories told about them in the majority culture. They offer interpretations of their lives that place them in the larger story of God’s gifts and purposes for humanity. Thus, far from being an inert account of their lives, these stories are performing the task of resisting larger structures and powers that would disempower, dehumanize, and degrade them. Furthermore, their faith they display is far from a simplistic, naïve take on God’s ways of being in the world. (pp. 129–130)

She goes on to argue that those who have been subject to violence, systems of oppression, substance abuse, incarceration, trauma, and extreme poverty offer an epistemological advantage to understand articulations of God’s grace and liberation in Christian theology. Dunlap argues that “Granting epistemological privilege to the oppressed means recognizing the limits of theological truths that arise in the context of greater financial, emotional, and cultural resources and being open to the disclosures of God in oppressive circumstances such as poverty, incarceration, and homelessness” (p. 130).

A broader theorization of religion from Thomas Tweed (2006) also shaped the way the Shelter Project thought about “crossing and dwelling” in the oral histories of our unhoused neighbors. Tweed emphasizes that “religion is about finding a place and moving across space,” paying attention to cultural flows and “complex processes” (p. 59). Tweed’s theorization is not limited to material objects or structural features of religion. However, it is a fitting understanding of religion in a broad sense and can be useful in considering the experiences of unhoused people who are literally and metaphorically trying to “make homes and cross boundaries” (p. 54).

Informed by this expansive theorization found in Tweed and in consideration of specific best practices for focused oral history interviews, the Shelter Project’s oral histories had program participants talk about their experiences. While we solicited discussion of what our neighbors may have experienced during the pandemic, we generally asked broad, open-ended questions. This is different from the dominant format of the life course oral histories used in most public history work. We hoped to achieve a carefully curated interview, one that provided interviewers with a script affording them some structure to ask questions about housing and home but that also let interviewees direct the conversation and share things that they wanted to discuss. In line with Tweed’s understanding of religion as finding a place and moving across a space, any of the questions that we asked could reveal important reflections on the experiences, practices, or processes whereby our participants find and make meaning. At the same time, we asked questions that lent themselves to participant sharing about their own material conditions, sense of place and space, and the ways their experience of a global pandemic and their local challenges with structural vulnerabilities inform these realities.

Participants were invited to share their names, age or age range, the gender with which they identify, race, ethnicity, religion, place of birth, or immigration status only if they desired to share those pieces of personal information. The guiding questions that student interviewers were invited to use in oral histories with Shelter Program participants were as follows:

- How did you get “here,” for example, what circumstances brought you to RCHP-AHC/the Shelter Project? Or what has your experience been over the past several months/during the pandemic?

- What is your relationship to housing stability? Have you ever experienced houselessness?

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected you personally?

- How has the pandemic affected your family, friends, community, neighborhood, etc.?

- What would you like others (advocates, neighbors, the general public) to know about your experiences with houselessness, or your experiences during the pandemic?

- What are your hopes for the future? For yourself, your family, or more generally for your communities, the country?

- Do you have a creative expression or creative outlet?

- Do you have any faith-based or spiritual practices or a religion that you ascribe to that you are comfortable telling us about?

Our student interviewers worked to generate and facilitate conversation with the interviewee without interruptions or value judgments, striving to be what my historian colleague O’Brassill-Kulfan described as “neutral supportive parties to the storytelling process, focusing on preservation, documentation, facilitation—not really interfering at all in the storytelling process” (personal communication, May 20, 2020). As it pertained to the question of religion and spirituality, our questions invited a conversation of these themes without assuming a Christian theology-centered approach. Rather, the questions about participants’ movements, housing, material conditions, family and community, creative expressions, faith-based or spiritual practices, and sources of information often revealed reflections on very Tweed-related subjects: how they have crossed, where and with whom they have found dwelling, and how the meaning they make and practices of connection with the divine or care for themselves and others help them to endure suffering, find joy, and affirm life.

These participant oral histories were curated and annotated for our project website to serve as a digital archive of this work (Figure 8). The annotations highlight how specific issues or vulnerabilities were reflected in the participants’ oral histories and to give readers from the public or from students engaging with this project statistics and additional reading that would enrich their understanding and sense of the scope of these issues in our local context and more broadly. And, as already noted, these transcripts were given to artists for their reflection and the creation of community-engaged arts interventions. The annotated transcripts were also used in the classroom, assigned to students in the Rutgers “History of Homelessness in America” course taught by O’Brassill-Kulfan in a new NBTS course entitled “Analyzing the Systems of Privilege.”

FIGURE 8

“Analyzing the Systems of Privilege” at NBTS was an ideal pedagogical home in the seminary curriculum for the Shelter Project’s iterative, adaptive, and collaborative scholarly and artistic interventions. That course began as a required antiracism workshop taught by outside facilitators. However, as the institution’s entire curriculum has in recent years sought to center questions of antiracism and social justice, the faculty moved from an outsourced workshop to a foundational class taught by an interdisciplinary team of faculty within the institution. The course underwent a significant structural revision as a result of collaboration with the present author, Janice Mc-Lean-Farrell, Beth L. Tanner, and Micah McCreary.

Recent revisions to the course have included more material on scientific racism, ecological injustice, human sexuality, and greater discussion of income inequality and houselessness, the latter additions being shaped by inclusion of materials derived from the Shelter Project. The teaching team for this course is gradually expanding to include other faculty members as a demonstration to students of institutional priority and in order to develop a shared language for thinking critically about power and oppression across the entire curriculum. The work of the Shelter Project and questions of housing insecurity in the United States provide local case studies through which students heard from their neighbors whose housing crises during the pandemic intersected with other vulnerabilities and social structures. Students explored how the seminary and its university partner engaged in this work by taking our lead from other religious and social service non-profit organizations.

Student work was directed toward a deep engagement with people’s stories and critical thinking about the possibilities and limits of religious and educational institutions. In addition to these annotated oral history transcripts, seminary students read scholarship about the crisis of houselessness in the United States and income inequality, such as Matthew Desmond’s (2017) Evicted: Poverty and Profit in an American City. They also consider other facets of houselessness connected to earlier work in the course, including the displacement of indigenous people, anti-Black racism that barred property holding, racially restrictive covenants and redlining, environmental racism, nativist and anti-immigrant sentiments and legal policies, gender and sexual violence, and the crisis of unhoused LGBTQ teens.

In discussion, students were able to discuss with instructors and fellow students where they were struck by practices promoting resilience, meaningful reflections on community, explorations of faith, and how these stories of their neighbors intersect with the broader analysis of social structures that they completed in preparation for their engagement with these oral histories. Selections from the oral histories used to jumpstart small group conversations included the following. On issues of sexual and domestic violence, students were reminded of one participant who shared:

Back in February, I was leaving my home due to domestic abuse and I was put in a domestic violence shelter for a couple of months prior to the COVID. … Then, once the COVID epidemic kind of sprung out, I was very limited to even leave the shelter and find housing. So, come about April and May, they were starting to tell me that I was starting to overstay my welcome and that my time limit there was very limited now. Even though, due to the COVID, I wasn’t able to find housing. So, when I reached back out to the church, they had actually had an apartment that was available for me and I was able to move in. (Fernandez, 2020)

On the topic of incarceration and returning citizens, they discussed another Shelter Project participant’s reflection:

I would like to make people aware that the individuals that are incarcerated are still people at the end of the day … A lot of the individuals that are incarcerated right now are not receiving the actual, proper care that some civilians are receiving on the outside … If we don’t show the gratitude of welcoming people back into our society, then we’re no more good than the bars that hold them in place. (Green, 2020)

Seminary student engagement in this topic promoted consideration of this person’s words as a structural indictment on US society, not only in a widespread apathy toward the prison industrial complex and the racist disparities in the rates of incarceration for Black and Latinx people but also in terms of the inadequate response of churches and non-profit organizations to those who are released only to find a lack of compassion and insufficient structural support to enable the reintegration of formerly imprisoned people into society at large.

A mother whose being unhoused involved struggles with her and her children’s medical challenges not only revealed her perspectives on struggle but also revealed some of her coping strategies and her reflections on gratitude and desire to help others.

I was currently homeless with my four children and I started reaching out to different resources … It was one of the worst times in my life, just being homeless with my girls and I didn’t want them to see me struggling and think that was the way to live. So, we basically just took it one day at a time and everything worked out. … Every day had to worry where we’re going to sleep at. Where we’re going to get food and different things like that. They were bringing us food, bringing us clothes. Giving us money to wash clothes, different things and we stayed there for seven months and they helped us out a lot. They helped us out a lot and I really appreciate it. A lot of times I cried because I didn’t think that there were people out there that would help and I was just thankful and I was like, when I see people, it makes me want to help other people. (Moss, 2020)

This mother’s story demonstrates how ability, health, and age or dependency often restrict one’s ability to pursue and retain employment as well as stable housing. These structures operate on top of other oppressive systems including anti-Black racism and educational and class structures. But these gathered quotes and the oral history of this mother prompt students to think not merely about a woman and her four children at the nexus of these vulnerabilities but also about how despite such struggles she refuses to be defined by them and in fact cultivates strategies for her survival and even aspires to help and care for others.

One oral history participant offered substantive engagement with questions of religion and community specifically, which provoked in-depth student engagement with the epistemologies and sources of our theology. His reflections spoke to his considerations of a complex religious response to material goods and physical sites, but also social goods and relationships and the individual and communal efforts to understand and relate to the divine. The selections from his interview merit quoting at length:

Well, the first thing I would like to say to the world to know about my community is that my community could be your community at any time. It is our community. It doesn’t belong to anyone. It belongs to all of us, so by coming to North Brunswick, this community will now embrace you and you will be engulfed into it. The love that’s within the community grows even during this pandemic. This pandemic only tested that love. This pandemic only tested the faith of the people’s hearts and the courage that was within their hearts. I commend the people. I commend you, and I commend those who are listened or who will be listening to this that they’re taking the initiative and the step further to be more connected, to be more one. What my community does and specializes in is unity. It doesn’t matter what your background is. It doesn’t matter where you’re coming from. If you’re here in our community, you are one of us. We embrace you fully, so I just see more and more of that every day. There is an improvement of it. It is never stale; it is never old. It’s always a reoccurring feeling, “Wow, I’m in this community. Wow, it’s such a fresh feeling. Wow, I get to wake up to this every morning. Wow, I get to actually live here.” To feel joy, to feel happiness is one thing, but to feel overwhelming joy from where you live at, it’s simply life impacting. When people see that you are joyful and you’re overwhelmed with joy, it’s contagious. It’s a positive energy that can’t simply be restrained. By you spreading that and it becoming contagious, it spreads to the next person and then to the next person. Therefore, you’ll have a community of people that are overwhelmed with joy and with love. You immediately get raptured in. If anybody was in the area or if anybody is looking or interested, North Brunswick is by far one of the best communities. I would say it’s great to live in and grow in.

… Church-wise, I just want to clear the air on some of the things. It’s not to be argumentative or debating. I’m not pointing anybody out. I’m not trying to put down anyone’s faith. What I’m about to say is to clear the air on the perspective. That’s what I have learned in life; it’s all about how you perceive things. I just wanted to clear up the perspective on Christianity and the Christianity that I have come to serve. As I said before, yes, I am Christian. I am spiritual, so I deal with the effects of what someone has done before me, and that is my savior Jesus Christ. When someone asks, “Are you Christian?” and they see it as religious, I quickly remind them this is nothing law-wise. Being a Christian doesn’t make me better than you. Being Christian doesn’t make me less than you. Being a Christian makes me a better me, so I take that better me and I try to show you what I have received by serving this faith, and living this faith, and embracing this faith. Of course, my prayers and hopes is that everyone comes to know the lord Jesus Christ. My biggest hope is that everyone comes to a perception or a perspective of understanding what Christianity is in its fullest and truest form.

… I am comfortable because it is still a work of God whether it’s religious or spiritual. I just want to make sure that everyone understands this perspective that religious is what is being seen outwardly. Spiritual doesn’t get too much of a spotlight because that’s between you and God. As far as any type of work, resource, or service in Christianity, or what the church is doing as a body, I say it’s very positive. I believe they’re doing a lot of donations to a lot of shelters lately, a lot of outreach ministries, and a lot of soup kitchen service help. As far as the church is concerned, they’re right on track with what they need to be doing as far as helping people in this pandemic. There is such a light. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a Catholic. It doesn’t really matter what denomination you are; people recognize what good is. Good doesn’t need a title. Good doesn’t need some big symbol. Good just needs to be recognized. Good just needs to be acknowledged. When someone’s doing good, they should be acknowledged. They should be surrounded by other people who have done good. That’s what the church does, and that’s what the church has been doing in this pandemic. … t’s a beautiful thing knowing that your voice matters, your actions count, and your purpose is realized. Like I said, good doesn’t need a title. You don’t need to call me a Christian. You don’t need to call me a good man, but my actions reflect the good man that stands before you. My actions or my words reflect the good Christian that stands before you. Just doing good onto others, just trying to go out of your way for that one more person today that you didn’t do for yesterday, or by going that extra step today to do something, even for yourself, it just shows the good that you have in life and that you should be living. That’s the abundant living that we was raised to come to understand and imitate throughout our life. (Green, 2020)

Seminary students were struck by this 29-year-old, formerly incarcerated and unhoused, African American college student’s reflections on community, Christian theologies and practices, and the appeal to social action rather than doctrine. Masters- and doctoral-level students in theology had an opportunity to give “epistemological privilege” to the religious reflections of someone who had experienced housing insecurity at the intersection of structural injustices. Students, through the voices of the participants and the oral histories, were able to hear from those who had experienced houselessness, what helped them survive, how they affirm life and human dignity, where they see the work and presence of the Divine, and how they understand faith or hope or joy in a world shaped by structural injustice and struggle. Interestingly, in the second year of teaching with these materials, in spring 2022, the NBTS class exploring the oral histories of the Shelter Project featured powerful perspectives from three of our own students, of different social locations, who were emboldened to speak of their own experiences being unhoused, temporarily and for long periods, in childhood and in adulthood. The conversation opened a forum for theological reflection for students who had long struggled to trust their own capacities to make meaning out of these traumatic experiences.

Listening to and with people in our local communities who are unhoused represents an attempt in my teaching and at NBTS toward a methodological shift away from academic knowledge and toward justice-seeking, community-engaged pedagogy. Asking for this kind of reconsideration alongside those experiencing houselessness, housing insecurity, or poverty offers a rare appeal in theological higher education but parallels and strives to affirm a similar call long made by Black feminist and womanist scholars of religion and theology. Layli Phillips and Barbara McCaskill (2006) argued for thinking and teaching that recognize the social locations and vantage points of Black women in their essay “Who’s Schooling Who? Black Women and the Bringing of the Everyday into Academe, or Why We Started The Womanist.” In Phillips’ section of the piece, she describes the pervasive and often default assumption in academic knowledge that the privileged and educated are thought to be the sources and arbiters of knowledge, while others are mere recipients: “It has been traditional to conceptualize education as emanating out from the academy to ‘the community’ and to conceptualize helping as emanating out from those with more socially sanctioned power and wealth to those who are considered disenfranchised or marginal.” Phillips elaborates that “This schematic has perpetually placed Black women—who have since their arrival in this country borne the brunt of the triple oppression of race, class, and gender—on the receiving end of every handout or supposed charitable act, as if to proclaim, ‘You are only needy; you have nothing to offer.’” She explores how this dynamic prevents Black women from being seen “as capable generators, interpreters, or validators of knowledge, even when that knowledge pertains to their own experiences.” She argues that this assumption hurts both Black women and the academy (p. 87) and offers a bold proclamation of the ways in which Black feminist and womanist approaches to epistemology and pedagogy offer a radically different way to know and teach:

Because Black women are intimately familiar with the experience of having one’s experience appropriated, exploited, misconstrued, and ultimately dismissed, Black feminists and womanists have developed an epistemological stance that demands the acknowledgement of one’s particular location prior to the pronouncement of knowledge. Furthermore, because Black women carry with them an Afrocentric cultural ethos that purports that reality is both spiritual and material, that self-knowledge is the basis of all knowledge, that knowledge can be obtained through the use of symbolic imagery (metaphor/parable) and rhythm (pattern), and that positive relationships among humans are the highest value (Myers 1991), Black feminists and womanists offer a methodological stance that is dialogic or conversational in approach, that views the relationship between researcher and research subject as collaborative and equal, that incorporates activism into the scientific method, and that does not discount the importance of spiritual as well as material (including concrete, everyday) scientific concerns (Collins 1990). (Phillips & McCaskill, 2006, p. 89)

This argument for a reorientation of academic knowledge and teaching is a bold rebuke of the academy as it currently exists. It promotes expanded forms of scholarship and an imaginative transformation of our institutions’ understanding of how we exist in relationship to our communities.

An affirmation of this insight could bolster the present argument for the value of a theological education that privileges collaborative, community-engaged scholarship and teaching. This would require an attention to methods, data, and output; this is accountable to and draws from unhoused and other vulnerable individuals and institutional partners from a broader community who center these people and their concerns. Within this framework, the present author (a White, cisgender heterosexual married male professor with socioeconomic status) must acknowledge personal privilege across these social structures and categories, the inadequacies of his own experience and location, and the inadequacies of traditional academic assumptions about the knowledge of houselessness and the vulnerabilities and identities of people who are unhoused. However, the transformative claim of the Black feminist and womanist approach is that rejection of racist, classist, gendered, and academy-centered assumptions opens up new ways to know and teach.

The Shelter Project aspired to put funds toward the urgent need of our most vulnerable neighbors, responsive to those who, during a global health crisis, fell through the cracks of other means of housing and other financial support. We sought to honor both spiritual and material needs. In oral histories, we sought to learn from and with those participants in the program, preserving their records of their cultures, their self-knowledge, their practices, patterns, and relationship. Deferring interpretive work to community-based artists, we hoped to find ways to situate interpretation outside the structures of academic knowledge, and we benefitted from artists whose own cultural commitments and social locations and experiences (some with personal experiences of being unhoused) honored participants’ oral histories and did so through symbol and image, sound, and rhythm. Privileging the vantage point of those who understand and have faced housing insecurity prioritized the experiences and sentiments of those whose perspectives are not usually centered in theology and religious studies. The Shelter Project prioritized responsiveness and responsibility to vulnerable individuals and partners in community, which in turn opened new sources of knowledge and ways of thinking that were community based and collaborative. As a result, what we learned and how we learned it led to interpretations that were community facing, teaching that was dialogic and conversational, and lessons attentive to the spiritual and material experiences of our neighbors that proved a source of collaborative transformation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Colin Jager (Department of English and Director of the Center for Cultural Analysis, Rutgers University), Co-Principal Investigator of the Shelter Project, and Co-Directors Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan (Department of History, Rutgers University) and Dan Swern (coLAB Arts New Brunswick) for their commitment to the work of creative social justice that resulted in our developing and implementing this ambitious project during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks also to the Henry Luce Foundation for generously funding the work of the Shelter Project and a cohort of Emergency Grant projects during a public health crisis. The Shelter Project benefitted from the guidance and support of the Luce Foundation’s Religion and Theology Program Director, Jonathan VanAntwerpen. The author would like to thank Seth Kaper-Dale and Carrie Dirks at the Reformed Church of Highland Park and the Affordable Housing Corporation and Austin Morreale of NeighborCorps, whose direction of direct services offered to our unhoused neighbors made this entire project possible. At New Brunswick Theological Seminary, thanks also go to President Micah McCreary, Dean Beth Tanner, Stephen Mann, and Cathy Proctor for supporting this innovative grant. Danielle Farah designed our logo and intern Jillian Singer helped with art installation events. Thanks also to Diana Molina of the Rutgers English Department, who worked on multiple parts of this project, the staff of the Rutgers University Center for Cultural Analysis, the Rutgers Public History Program, and Natalie Raichilson at the Rutgers University Foundation. We also are grateful to the students who conducted oral histories or served as student podcast producers for the Shelter Project, and for the training provided by the Rutgers Oral History Archive. Mary Gragen Rogers deserves much credit for making possible our public facing art installation, and Scott Gurian’s journalistic and audio-engineering expertise and care cannot be praised enough for turning our project’s work into an accessible and well-produced podcast. Finally, special thanks to all the community artists who contributed to the Shelter Project and to those who received services who were also willing to share their stories through recorded oral histories.

REFERENCES

- (2017). Evicted: Poverty and profit in an American city. Broadway Books.

- (2021). Shelter theology: The religious lives of people without homes. Fortress. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1khdps5

- (2020). Oral history interview/Interviewer: E. Young. Shelter Project. https://shelternj.org/oral-histories/blog-post-title-two-rzp57#transcript

- (2020). Oral history interview/Interviewer: E. Young. Shelter Project. https://shelternj.org/oral-histories/josh-green#transcript

- (1970). Notes for a theology of liberation. Theological Studies, 31(2), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/004056397003100201

- (2020). Oral history interview/Interviewer: A. Jitan. Shelter Project. https://shelternj.org/oral-histories/blog-post-title-one-sgxha#transcript

- , & (2006). Who’s schooling who? Black women and the bringing of the everyday into academe, or why we started the womanist. In L. Phillips (Ed.), The womanist reader. Routledge.

- The Henry Luce Foundation. (2022). Luce Foundation makes $3M in emergency grants to support communities and organizations affected by COVID-19 [Press release]. https://www.hluce.org/news/articles/luce-foundation-makes-3m-emergency-grants-support-communities-and-organizations-affected-covid-19/

- (2006). Crossing and dwelling: A theory of religion. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674044517

- (1983). Black religion and Black radicalism: An interpretation of the religious history of the Afro-American people ( 2nd ed.). Orbis.

ARTICLE

(2023). Shelter and dwelling: A pandemic response to houselessness and community-engaged pedagogy in theological education. Teaching Theology & Religion, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/teth.12643